Investing in a Life of Meaning and Happiness

Apply online and begin your next chapter.

Tour campus, meet with admission staff and get to know Juniata.

Identify your passions, explore endless opportunities, and design your own education.

Explore Juniata’s campus with our virtual tour.

Meet your admission counselor in your area.

At Juniata, you won’t simply be a recipient of knowledge—you will be a participant in your own learning.

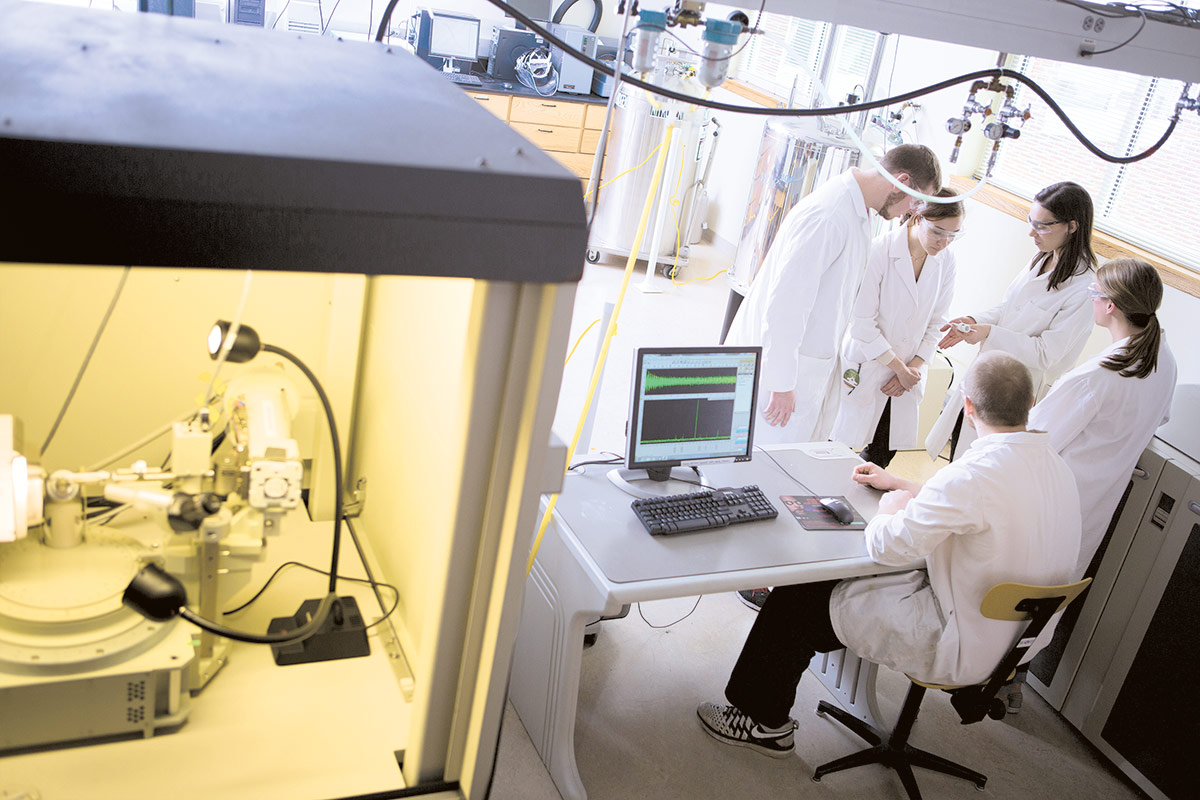

Here, undergraduate research is a prestigious opportunity to work in groups, network, receive feedback, have results published—and learn humility and tenacity along the way. You’ll go into the field, collect data, analyze it, and then contribute to the body of knowledge associated with your field of study. It all starts with the relationship you develop with your professor—a true scholarly partnership that launches in college but that lasts through your entire career.

We asked a few of our professors what their students learn from conducting undergraduate research. Here are their stories of students’ epiphanies, frustrations, perseverance, and, ultimately, success.

Related Content

History Professor Alison Fletcher never gives students a topic to write about; instead her students find a topic they are passionate about. In her classes on Crimes Against Humanity, Southern Africa, and Disease, Medicine, and Empire, students write a one-page proposal about what they would like to be the focus of their research.

“Usually, they come up with topics that two to three books could be written on,” says Professor Fletcher. So, she invites them to her office to discuss.

“Many of the students who take my classes are not history majors. As a result, topics are wide-ranging. And I love that. My students have recently authored papers on HIV/AIDS in South Africa, children in the first World War, and the role of music in ending apartheid.”

A student’s proposal then becomes a thesis statement. Ideas coalesce into passions and are shared with classmates.

“Through the process of researching and peer editing, students at Juniata come to think of themselves as a community of scholars,” Fletcher says. “The class develops an interactive culture.”

Fletcher says that the ultimate goal is for each project to be student-inspired, and she tells students how they’ll know if they have accomplished that important feat:

“When they think of their work in the shower, they know their work has come alive. The voices of people from the past whisper in their ears, and they can’t ignore that.”Alison Fletcher, professor of history

“When they think of their work in the shower, they know their work has come alive,” Fletcher concludes. “The voices of people from the past whisper in their ears, and they can’t ignore that.”

Dennis Plane, professor of politics, tells students who are doing promising work to give it away to someone else.

In his class, the first stage of research is to build a data collection plan, a plan that must be so specific that if another person were to implement it, the result would be an exact replication of the original.

In their first iteration of a plan, students generally miss the mark. And that is okay.

“It’s a learning experience like everything else,” Plane says. “You have to do it a few times before you get it right. They get frustrated that I want them to go back to the fundamental research design again and again, but that’s the reality of the discipline. Through weekly meetings, we hone their method, and they begin to adjust and collect data anew.”

But that’s just the beginning.

Students submit applications to present their research at venues such as the National Conferences on Undergraduate Research (NCUR) or the Pennsylvania Political Science Association. At these conferences, they field questions—a lot of them—and that causes them to revisit their plan yet again.

"From the most initial development stage to publication, students discover that the best research is an iterative process."Dennis Plane, professor of politics

“From the most initial development stage to publication, students discover that the best research is an iterative process,” Plane says.

And it’s a process that never really ends.

Take the case of Josh Scacco, a 2008 graduate of Juniata, who is now an assistant professor of political science at Purdue University.

“Josh researched the voter registration process,” Plane recalls. “We asked different students at different universities to complete voter registration forms and then analyzed the forms for errors.” Josh presented his first cut of the paper at NCUR but polished it over the years. He published it in the Journal of Political Science Teaching.

Professor Plane was a co-author on student Scacco’s publication.

So, no matter how long you persevere with a research project, even well into your doctoral work, it will never be totally your own. Juniata faculty and all your peers who tested your plan and questioned you along the way are ongoing partners in your success.

Ursula Williams, assistant professor of chemistry, knows she’s not supposed to have favorite students. But, it’s obvious that some students excite her more than others.

What’s not so obvious is that her favorites aren’t the superstars. It’s the students who work really hard for a B- grade. “For them, undergraduate research can make all the difference.”

Williams explains that students who don’t perceive themselves as the best in the classroom find their home in the lab, where they receive individualized attention and have space to think quietly.

“I had a student who graduated last spring,” Williams recalls. “She did fine in class but wasn’t an A student. She came to me one day and said ‘I want you to know I’m trying so hard.’ I realized she compared herself with the class superstars and felt like she was always falling short. So, I invited her to do summer research with me.”

Williams said that, although the student started out very nervous, pointing out that she didn’t know how to do synthesis, for example, she did a great job in the lab. She was very organized and her lab notebook was immaculate.

The next summer, this rising star trained another student who would take on her work so that she could present her research at the Landmark Symposium and at regional American Chemical Society (ACS) meetings. This was her turning point, when she gained her confidence as a chemist and a scholar. “She saw that she made her own success.”

"For all students, actively engaging in solving problems empowers them. Students are shocked at what they can do when they put their minds to it."Ursula Williams, assistant professor of chemistry

"For all students, actively engaging in solving problems empowers them. Students are shocked at what they can do when they put their minds to it."

“The experience of presenting at those meetings is a big deal to students. The presenters around them are graduate students and professionals,” Williams says. “At the national ACS meetings, there are 15,000 people involved in these conferences. Students realize, at those moments, they’re one of the experts gathered and they have important contributions to share.”

Juniata College

1700 Moore Street

Huntington, PA 16652

Juniata College

1700 Moore Street

Huntington, PA 16652